Throughout my trip to Malta, we came across many churches, each breathtakingly more beautiful than the next, and it seems to me that our tour guide Mr. Zammit saved the best for last because Saint John’s Co-Cathedral literally left me speechless.

Located in the heart of the fortified city of Valletta, its outer walls are deceivingly plain, for what lies beyond the heavy ancient doors is one of Europe’s most ornate Baroque interiors. No amount of words or camera captures can summarize the immaculate beauty of this Baroque masterpiece that was built in 1572 by the Knights of St. John. It is seeped in centuries of history, painstaking artistry and a deep-rooted sense of faith that went on to become a monument to a chivalric order that shaped Mediterranean history.

Tombstones of the Knights

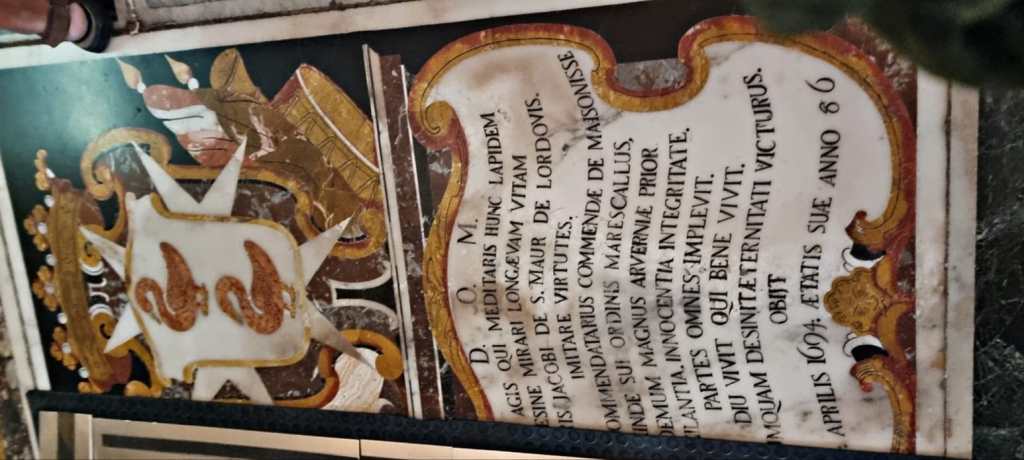

You literally walk into history at the first step for beneath the gilded ceilings and ornate side chapels lie nearly 400 tombstones of knights from across Europe who served and sometimes died defending Malta and the Catholic faith, especially during the famed Great Siege of 1565. Their legacy is etched not only in history books, but literally in the floors of this cathedral.

Each tombstone is inlaid in marble, marking the resting place of a Knight of the Order of St. John. These tombstones are works of art, each individually decorated with skulls, hourglasses, swords, and coats of arms, symbolizing mortality and military honor.

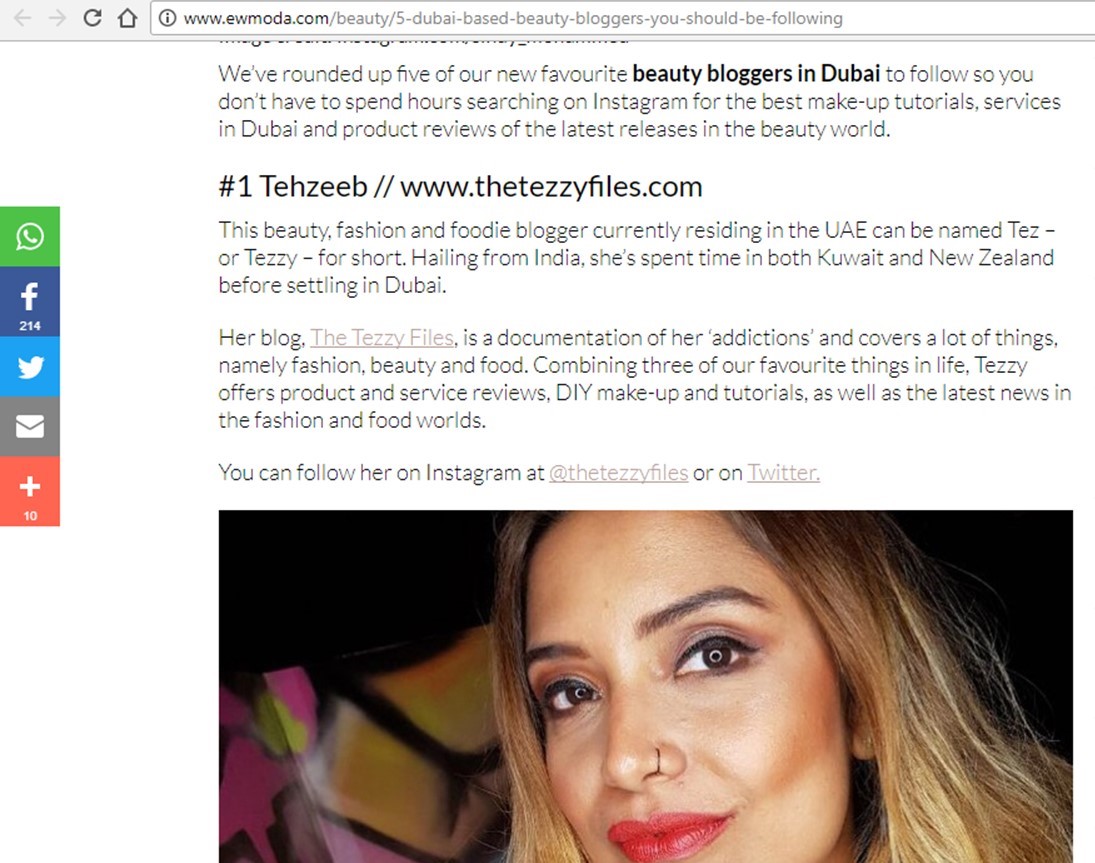

We stepped onto this tombstone at the entrance of St. John’s Co-Cathedral, and its Latin script read out a morbid greeting…

You who steps on me today, someone will step on you tomorrow.

The Language Chapels: Europe under one roof

The Knights were divided into “Langues”, or tongues, based on their regions of origin. Each langue had its own side chapel, and in true knightly fashion, each tried to outdo the other in artistic patronage. These chapels were therefor far more than just devotional spaces; they were a silent competition of prestige, each with its own story of loyalty, power, and piety.

Langue of Aragon: Rich in Spanish iconography, with tributes to St. George and warrior saints.

Langue of France: Dramatic sculptures and bold marble work, reflecting the grandeur of French nobility.

Langue of Italy: Known for its Baroque flourishes and artistic complexity.

Langue of Germany: Darker, more austere decoration, hinting at Gothic roots.

Langue of Castile, León, and Portugal: Arguably the most lavish, a chapel of almost overwhelming splendor.

The Masterpiece in the Oratory: Caravaggio’s Beheading of Saint John

The absolute showstopper at Saint John’s Co-Cathedral for any art enthusiast is this masterpiece. Painted in 1608 by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, it remains his largest surviving work, and the only painting he ever signed; not in ink, but in the red blood spilling from John the Baptist’s neck.

Caravaggio was a renowned Italian artist, but also a man of hot temperament. After killing a man in a brawl in Rome, he took refuge with the Knights of St. John. By 1608 he had the rare of honor of being knighted by the Order. This was uncommon for a foreigner, especially one with a violent past. However, he got into trouble once again and lost his honor, and went on to create this masterpiece during his imprisonment.

Caravaggio uses his signature chiaroscuro (dramatic light and shadow) to emphasize the cold, slow horror of state-sanctioned violence. The painting depicts the moment after the execution where Saint John is seen lying slumped on the ground in a pool of blood. The executioner, visibly at unease, is about to draw a knife to finish the job. A woman holds a platter, waiting to be served the head. Two prisoners, voiceless witnesses, watch in horror from the shadows.

The masterpiece is signed in the blood of the decapitated martyr, and reads “f. Michelangelo” (short for fra Michelangelo), the name Caravaggio took upon joining the Order. It is his only signed piece of art. Historians debate on whether this act of signing in blood was one of defiance to his fugitive state of affairs, or a solemn act of repentance.

Despite being a fugitive knight, a man of violence, and a genius with a brush dipped in blood, the Knights preserved Caravaggio’s masterpiece and gave it a place of honor in Saint John’s Co-Cathedral. Today, it remains in the same oratory, an solemnly dark ode to a violent past.